What is the deal with violence in Chicago?

March 2, 2016

Hadiya Pendleton. Jonylah Watkins. Laquan McDonald. These are just a few names of the individuals who were victims of high profile shootings in Chicago over the past years. However, only one of the three aforementioned cases was a police shooting. On October 14th, 2014, 17-year old African American Laquan McDonald was shot sixteen times by Chicago Police Officer Jason Van Dyke.

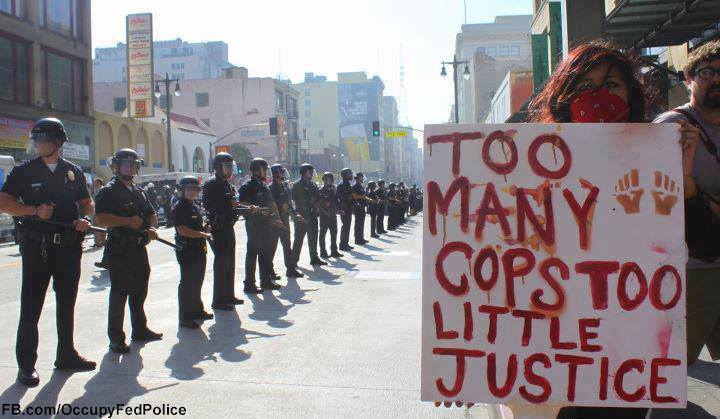

The now infamous shooting has gained recent media coverage once the police video of the shooting was released on November 24, 2015. The video was highly graphic in content and jolted many people out of their comfortable naiveté and prompted the city wide question: how much longer would Chicago allow its police officers to commit such egregious acts? Since then, Black Lives Matter activists have raised protests and have blocked Black Friday shoppers from stores on November 27, 2015. Chanting, “Sixteen shots” and other slogans, they marched on Michigan Avenue to raise awareness for the case.

Primarily controversial for the excessive deadly force used by Officer Van Dyke, other issues were raised by the dubious state of the videos of the shooting. Interestingly, only two of the dashboard video recordings have been known to exist although there were five police vehicles with dashboard cameras on the scene. Despite the mandate that Chicago police officers are required to make sure their video systems work, there has been no evidence of any other video recordings. In addition, the video footage that has been released did not contain audio.

Although Chicago Police dashboard cameras automatically record audio, the most contentious point about video recording of the shooting has been the possible recording from a nearby Burger King. There was a security camera at the local restaurant that may have captured the shooting, but 86 minutes of that footage of the shooting was missing. The manager of the restaurant claimed that on the night of the shooting, five Chicago police officers gained access to the video and passwords on the equipment, and that by the time the footage had been requested the next day by the Independent Police Review Authority, a committee which independently reviews controversial police activity, it had been erased. Later, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigators stated that the Burger King tapes had not been tampered with, but there was enough suspicious activity with this case that it began to garner public interest, and more and more people began to demand an answer-and consequently, justice.

The combination of racial bias and militarization of police forces have contributed to an enormous uptick in police involved shootings and recorded cases of police brutality in the past decade. How can the problem of police brutality be solved? There is no one single way to stop it, but there are different steps that can be taken together to do so. Zak Cheney-Rice of Identities.mic has outlined fifteen different things a city can do to end police brutality. These include specifics, such as the removal of military grade weapons from city police and involving the community in big decisions. Cheney-Rice writes, “Every city should have an adequately funded community oversight board with significant investigatory and disciplinary powers. They should reflect their communities, especially the elements of their communities most affected by police abuse. The majority of these committees should be democratically elected.”

The biggest issue with cases of police brutality though is the fact that police officers are trained to be armed patrolmen, not members of the communities they are protecting. They are trained to handle rough situations: people with guns, car chases and foot pursuits. The Washington Post writes that new recruits usually spend about 60 hours learning how to handle a gun. That is good, right? We want to have tactically trained men and women to help us. But guess how much time they spend learning how to de-escalate tense situations or properly handle the mentally ill? Eight hours apiece, according to the Police Executive Research Forum, which is a major problem. To start, police officers should be trained on how to develop better relationships with their communities. The report recommends that recruits be “thoroughly and professionally trained on procedural bias and fairness, implicit bias, institutional bias, relationship-based and community interaction, crisis intervention, mediation, conflict resolution, de-escalation and minimizing use of force, coping with mental ill individuals, increasing language proficiency and cultural competency and documenting, preventing and addressing sexual harassment, abuse and assault.”

Some people express doubts that this kind of thorough training will use tax dollars, but if the money we pay to the city is not being used to protect every person in it, where else would it go? Would you rather a more educated police force that can do as much for minorities as it can for others with higher taxes, or an uneducated task force that continues to deal harm to underrepresented communities because of the lack of funding for better training programs?

The choice is clear. Victims of police brutality like Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, Eric Garner and, Chicago’s own, Laquan McDonald would have appreciated the effort.

Amy • Mar 6, 2016 at 6:55 pm

Isn’t black on black crime the REAL issue in Chicago?