Is There a Correlation Between Race and Accidental Deaths?

March 3, 2022

On January 9th, 2022, an apartment fire in the Bronx killed 17 people, including eight children. More than 60 people were hurt, half of whom suffered life-threatening injuries.

According to FDNY Commissioner Daniel Nigro, the fire was caused by a “malfunctioning electric space heater” located in the bedroom of a duplex apartment that occupied the second and third floors of the building. Investigators later found that the smoke spread through the building as a result of two malfunctioning self-closing doors, causing deaths throughout the building. All of the persons killed in the fire died from smoke inhalation.

Experts believe that the accident could have been prevented with sprinklers, functioning doors, an alarm system, and a working heating system, preventing the need for supplemental heat.

The four deadliest fires in New York City since 1990 have now all been in the Bronx, which has an estimated 43% Black population. Most of these fires can be traced back to unclosed doors or space heaters.

The Bronx fire was also the second major residential fire in the United States within a one-week period, occurring four days after a fire in Philadelphia public housing resulted in 12 deaths.

So what does all of this mean? What more is there to say about these accidental deaths?

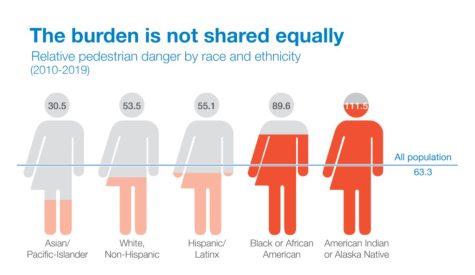

Incidents like these, which occurred in predominantly Black neighborhoods, are commonly labeled as accidents. This goes hand in hand with the fact that statistically, Americans who die of accidents, are disproportionately people of color.

These accidents are most likely to happen to impoverished people of color. So is it really an accident? An accident is unpreventable, but there is nothing unpreventable about these incidents. These happenings can not be fully blamed on individuals or our actions when in reality it is a larger pattern that can be halted. There are steps that federal agencies should be taking to protect us, but they become underfunded and people grow more prone to these accidents, especially people of color.

This trend goes for more than fires, as it is proven by data for traffic accidents, poisonings, and much more. But the largest inequality in accidental deaths is that of police-involved harm, which shows that people of color, especially African Americans, are at greater risk than white people. Researchers from Rutgers University, Washington University and the University of Michigan examined the risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex. The study, based on data from 2013 to 2018, found that police violence is a leading cause of death for young men in the United States.

Accident is not the right word for these horrors. We can not use it as a word to avoid discussing deeper issues. These matters have been growing, just like the racial and economic gaps that have been rapidly expanding. To inaccurately call something an accident, we are choosing to stay comfortable and not ask more questions.

Next time you hear something labeled an accident, figure out the history of related incidents, look at trends, and how we can avert another situation like this? Without this process, we are stuck in a racist, classicist, systematic cycle of tragic accidents. There is immense reform needed before we can create a more just and equitable strategy to keep everyone safe, not just the wealthy white population.

To learn more about the trends surrounding accidental deaths, make sure to check out There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster—Who Profits and Who Pays the Price by Jessie Singer. Published on February 15th, it covers current and historical racial and economic disparities in accidental deaths.