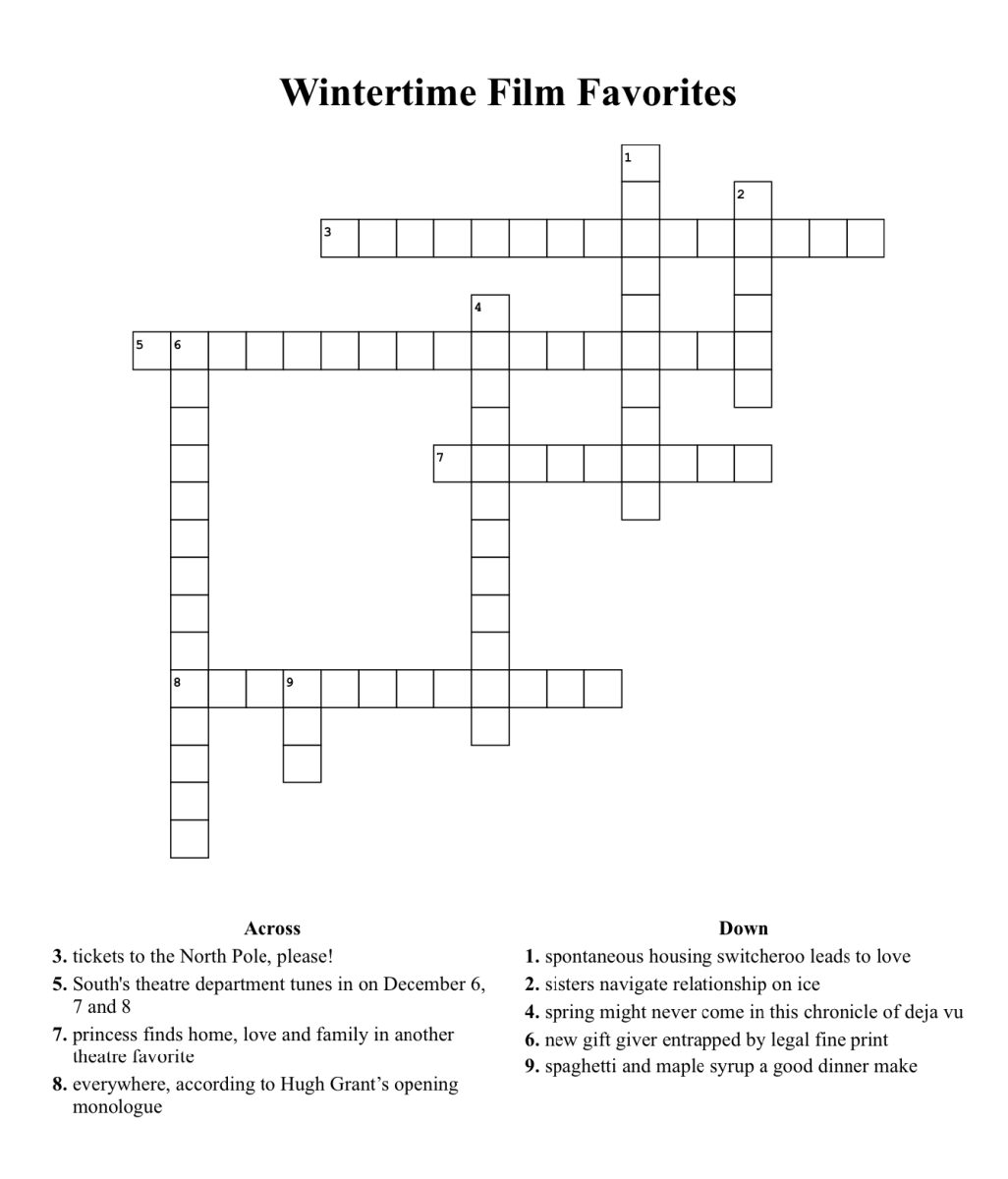

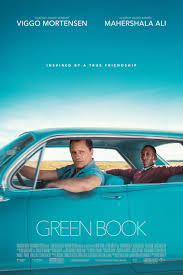

“Green Book” Review

March 11, 2019

When highly unpopular businessman Donald Trump won the presidential election in 2016, the nation entered an immediate uproar. Some speculated that this outward distaste for president Trump would lead to a powerful, revolutionary movement of activism and art from the youth and minority groups that had expressed distaste for Trump at the greatest proportions. Although this has proven true to some extent, the majority of the mainstream media and art has only resorted to complaints of Trump’s Twitter typos and orange skin. The newest Best Picture winner from the 2019 Academy Awards, Green Book, is an almost humorously on-the-nose culmination of this slow development toward safe, boomer-core liberal mumbo-jumbo that gently fosters the type of political leanings that allow someone like Donald Trump to take office.

The US is in the midst of a volatile political era, including the threat of various time-sensitive issues. While people gripe about the quality of Trump’s hairpiece, climate change threatens everyone’s way of life. During a drastic time such as this, it is important not to incentivize the centrism expressed in works like Green Book. As a film on its own, it is fine, but winning Best Picture was the worst thing that could happen to Green Book in terms of its standing as a piece of art. Its Oscar win was met with a resounding groan and for good reason. It is probably best to avoid the topic of the demographic of Academy voters, as this topic has been beaten into the ground.

Green Book follows oafish Copa-Cabana bouncer Tony Vallelonga (Viggo Mortensen) and world-class pianist Dr. Don Shirley (two-time Oscar winner Mahershala Ali) as they travel through the deep south on Shirley’s concert tour. Over the course of their journey, they encounter many intolerant whites throughout their journey, and at many points Shirley impacts many peoples’ lives beautifully with his musical talents. The two men bond slowly but surely, with Shirley beginning to see through Vallelonga’s rough exterior and Vallelonga realizing the hardships Shirley goes through as a gay man of color.

A common criticism of Green Book is that it uses the “white savior” trope, meaning that it portrays Vallelonga as a crusader for Dr. Shirley that swoops in to solve the injustices that he faces. This criticism is furthered by the context of the making of the film as it came under fire from Dr. Shirley’s family for being an unrealistic portrayal of the role that Vallelonga played in Dr. Shirley’s life. According to an article in Shadow and Act, Shirley’s living relatives were effectively excluded from the filmmaking process. Additionally, Shirley’s relatives took issue with the portrayal of Dr. Shirley as a man out of touch with black culture, noting that Shirley took part in the famous Selma march and was friends with important black cultural figures such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Duke Ellington and Nina Simone.

Knowing of director Peter Farrelly’s previous work (There’s Something About Mary, Shallow Hal, etc.), the liberty taken with the truth seems to make more sense. Farrelly’s prior films are classically cinematic and always fictional, maintaining an ethereal sense and fitting neatly into a tight three-act structure. Farrelly (along with brother Bobby Farrelly) has directed some of the best comedies of all time. It is interesting that Green Book is as tone deaf as it is as many of the Farrellys’ other works have incredibly nuanced themes for being escapist comedies, touching on self-worth, ableism and the changing role of the male in society. In light of the Farrellys’ prior thematic success, one can only speculate what caused Green Book to miss the mark. Possible culprits are Bobby Farrelly’s lack of involvement, the unfamiliar genre, or the first true story any Farrelly has filmed. Regardless of the source, it stands that Green Book does not hit its mark thematically.

The issue of the “white savior” trope in Green Book could be chalked up to the struggles of a director accustomed to zany, surreal comedies, but Farrelly should not get off the hook that easily. Green Book seems as if its inception was so that white people could pat themselves on the back in regard to race-related issues. It is telling that Spike Lee’s BLACKkKLANSMAN, a more radical film that approaches racial issues in a bolder, more astute way as well as simply being a better movie overall, won only one award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Frankly, it makes sense that the Academy would favor more centrist films. The award show itself is a business venture; according to Forbes, the 2017 Oscars garnered $115 million in advertisement revenue (despite relatively low ratings). One of the main principles of investment is that stability is preferred. What better way to ensure stability than to establish a made-up standard for what makes a movie “good”, and then offer top awards to the safest movies that stay within the confines of this standard? This strategy is agreeable, it has established the Academy Awards as a yearly cultural fixture and, most importantly, it has worked for ninety-one award shows straight.

Ironically, Spike Lee experienced a bizarre parallel to this year’s Oscar loss thirty years ago in 1989. Lee’s Do the Right Thing, one of the most famous, important films in the history of the medium was not nominated for Best Picture in the year that Driving Miss Daisy won. Do the Right Thing was also noted for its head-on approach to important racial issues relative to the rather conservative and safe Driving Miss Daisy. By picking Green Book, the Academy confirmed an unfortunate suspicion: we are in the same place we were in 1989. We have allowed ourselves to be commodified into desensitization, and as a result, we remain in the same place culturally thirty years after Lee’s infamous Oscar snub.

Hopefully the backlash to this Best Picture win will be the first step toward the death of the Academy Awards, and in turn, the death of objectivism and commodification of film. Perhaps this is wishful thinking, but maybe if we were to not afford as much value to award shows that profit off of centrism and instead treat art the way it should be treated, more radical ideologies could permeate into the American subconscious and art could become a valuable tool toward progression.

As for director Peter Farrelly? We can only hope that he’ll repent for this stain on his filmography in the form of a sequel to Me, Myself & Irene.