The Intersectionality of Environment and Race

March 4, 2022

Black History Month is not only a time to honor the important African American members of the United States present, past and future, it is also a time to educate society on the racial disparities that are more prevalent now than ever. While protesting in 2020 brought forth the conversation of racial inequity in the justice system, there are still many other areas of injustice that have a chokehold on the U.S. A largely ignored topic is the correlation between environment and race. Although in recent years climate change and environmental movements have been the talk of the town, many do not look at the issue from the perspective of people of color, who are often the ones facing the largest consequences. They face greater impacts such as being predisposed to certain diseases due to proximity to environmental hazards and pollution. Staff writer for The Atlantic, Vann R. Newkirk II, goes as far as to argue that ‘ Environmental Racism is the new Jim Crow’.

One major problem people of color face is proximity to environmental hazards. Professor John. A. Powell at University of Berkeley California conducted a two year study working with the United Church of Christ in 1986, showing that the majority of toxic dump sites around the nation are located in Black and Latinx communities. The Commission of Racial Justice within the United Church of Christ received data from mostly public review, for those by both commercial and uncontrolled hazardous waste sites. Powell also stated that the location of these sites was not necessarily due to socioeconomic factors, considering a Black person making over $60,000 a year is more likely to live next to a toxic waste dumping ground than a white person making less than $10,000 a year.

In general, environmental hazards such as heavy pollution disproportionately affect communities of color. The United States 2010 Census reports show that African Americans make up 13 percent of the US population, but an astounding 68% live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant, compared to just 56% of White Americans. Additionally, more than one million African Americans live ½ mile or less away from natural gas facilities, and over one million African Americans are facing a “cancer risk above EPA’s level of concern” due to unclean air from those very same factories. Similarly, African Americans are 75% more likely than White people to live in areas near facilities that produce loud noise, odor, traffic, or emissions that are known to have an unmediated impact on the community. Researchers from Environmental Protection Agency’s National Center for Environmental Assessment found that people of color are not only more likely to die of environmental causes, but also that more than ½ of people who live close to dangerous waste sites are people of color. This is likely due to deeply ingrained beliefs that came out of American slavery, when African Americans were evaluated as “disposable”, and therefore sent to work in undesirable conditions deemed too dangerous for white workers. For years, political neglect and discrimination have kept Black families in dangerous environments.

Furthermore, Black people are much more likely to develop environmentally related health problems, such as asthma or lead poisoning. Princeton University found that 13.4% of African American children suffer from asthma, in comparison to only 7.3% of White children, meaning that Black children are almost twice as likely to develop the condition. Also, communities such as Flint, Michigan, a heavily black community known nationally for its illness-inducing and horribly lead-filled water , backs up the statistic that Black children are twice as likely to suffer from lead poisoning than White children. In Flint, a town of 40% impoverished African Americans, a test by Virginia Tech researchers found that local water had lead levels of 13,200 ppb, which is over 7000 ppb over what is considered a hazardous amount. When community members reached out to complain about the dangerous substances in their water, they were told by the Environment Protection Agency to ‘relax’.

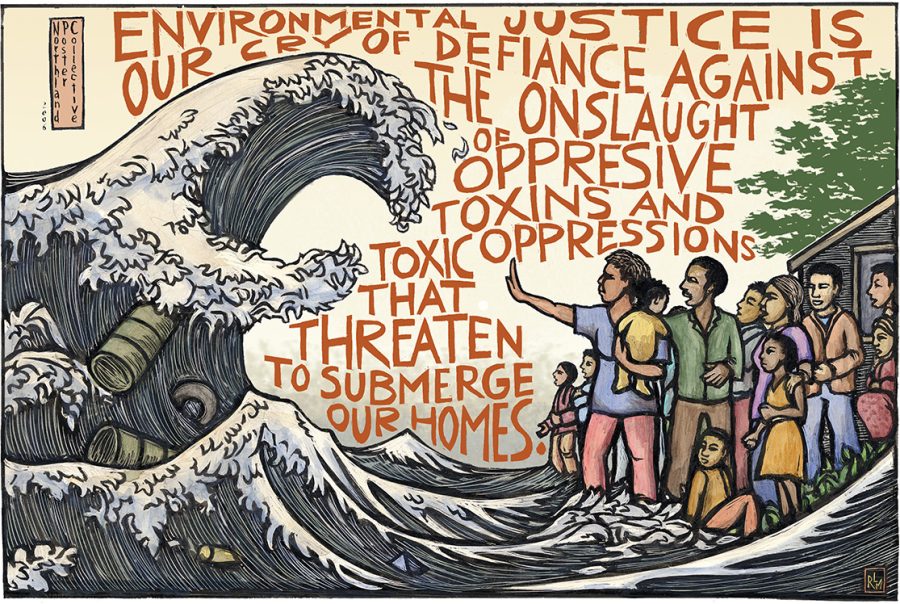

Collectively, it is evident that Black Americans have been systematically and perpetually put in an unfair place when it comes to the environment. It is affecting not only their health and neighborhoods, but also their livelihoods. During this Black History Month, it is important that Americans as a society think about their role in the burden of environmental racism, and do everything possible to stand up for a brighter, cleaner and more equitable future.